The Dead Planet Theory

No one does anything, the bar is lower than you think

Everyone loves to talk about the Dead Internet Theory, but less often discussed is how few people “do things” in any venue or on any platform. This phenomenon is known by several names, including the Power Law, the Pareto Principle, and the 80-20 Rule. One example of this phenomenon is that 10% of Twitter users account for 92% of tweets. This dynamic can be seen in interpersonal relationships, hobbies, and careers. You can use this to quickly rise to the top, or purely to get a little more enjoyment out of the things you do day to day. In the scope of all of creation it can be hard to see the impact of this principle in action, but by separating things, events, and people by category and interest it quickly becomes apparent.

A great way to visualize how few people participate in life is by looking at rank distributions of competitive games. In Marvel Rivals, every player is initially Bronze 3 and ranks up from there. Almost everyone who actually plays the competitive mode of the game will rank up no matter how bad they are at the game, so we can see that over 30% of the playerbase has never even played the competitive mode. Simply by playing a competitive match, you are ranked in the top 70% of the playerbase. We can look at other activities and interests, such as film, to further reinforce this point.

In all fields, the best quickly climb to the top, so it doesn’t take that long to identify who they are, and to find out what they are doing. I'm mostly focusing on the start of the journey, but things get truly exceptional if you can show long term consistency. Just doing things in general is admirable, but intentional training is the true starting point.

The thread above has several great examples, and a common element is that plenty of these are activities that many people do, but few people train. Chess is a great demonstration. On chess.com, you can learn about move-sets by playing, as the app won’t let you make an invalid move. Many people play chess, but few people train chess. Just by spending an hour learning a single opening, you can be substantially better at chess than someone who has played chess for years without ever training. This leads into my next point: no one does the reading.

When I was working in tech, I noticed a particular API parameter would reflect any input, and I wanted to know why it was doing that if it was supposed to be a simple identifier. I asked several coworkers before I found someone who knew, and we went into a meeting room where he walked me through all the different service calls that interacted with that identifier, and the reasoning behind it being dynamic. He told me that it had been that way for years, and was mostly unused these days. He also told me I was the first person that had asked about it in 2 years. I ultimately found a major vulnerability in our logging because of this innocuous identifier most people ignored.

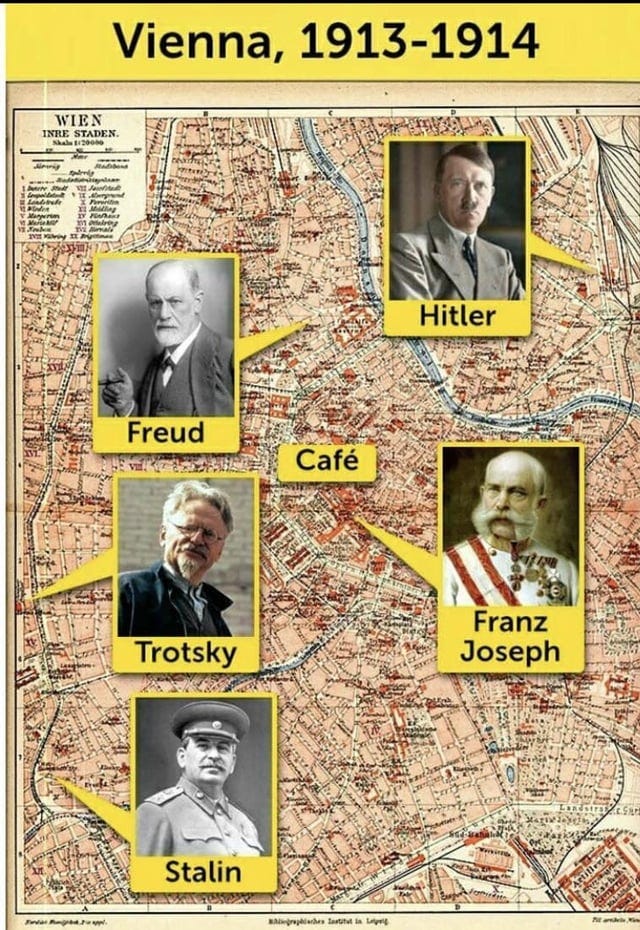

This brings me to my main point, actual actors are rare and tend to coexist. If I were to write a fictional story, and set this many characters of such magnitude in the same city at the same time, people would think the premise was absurd. The reality is you will see this play out in countless ways with countless groups. A common example is a simple friend group. You generally have core members, who are core not because they are more attractive or popular (though to be honest this is sometimes the case), but because they actually show up. When I was organizing frequent events, as long as I could convince 2 or 3 other people to go to an event, I would often get 10 to 15 people actually showing up. There would be an inner circle of 3 or 4 event planners, an additional 3 or so consistent attendees, and 20+ people that would rotate in and out. From the outside it may look like 5 people were more popular than than the others, but the reality is that without that core, the other 20+ rotators would just never hang out with each other.

From a career perspective there are plenty of ways to “do the reading” or to get ahead. A boomer classic is to speak to a manager and give a firm handshake, the seed of good advice is still there. By being willing to apply to jobs, or studying and practicing for interviews, or asking for a promotion, or by researching salary and negotiating well, you can quickly and substantially elevate yourself. An important thing to remember is that if you want other people to do things for or with you, think about their perspective or challenges and make it as easy as possible for the other person to help you.

A work example is if your job uses a “promotion packet”, which is common in tech, you can literally write your own promotion packet and get your manager to sign it for you. Normally after a couple years at a big tech job your manager will ask you if you want to go for a promotion. You’ll then spend the next year increasing your scope and taking on more complex projects. If that year goes well, in your next performance evaluation your manager will say he plans to promote you in the next six months to a year. He will then start reaching out to other managers or individual contributors you worked with over the year. He’ll get feedback from each person, and all of your feedback providers will often have packed schedules and take weeks if not months to provide their feedback. Your manager will then compile said feedback, summaries of your projects and achievements, and your performance reviews into a document. This is your promotion packet. Wanting to push for promotion is already rare, and going so far as to write your own packet makes it way more probable that you get the promotion you want, and it can potentially push your promotion forward by years.

An added benefit to doing things, or being in the arena in general, is that by participating in the game you enable luck. If you never leave your apartment you can’t have a serendipitous run-in with your future spouse. By entering the ranks of the doers, things can happen to you as well. If you don’t apply to a job you don’t 100% meet the requirements for, they aren’t going to email you a “sorry we missed your application”, they’ll go on to someone else who isn’t a perfect match, but was willing to apply. Too many things in life reward action for you to live in a state of stupor.

If you start anywhere, start with simply doing something. For socializing, this can just be showing up when people invite you to something. If you’ve started doing things already, consider “training”. This can be doing the reading, hosting events yourself, or even literal training. This will allow you to quickly distinguish yourself, and it will make your life substantially more fulfilling. Go forth and remember that with even minimal effort, you can elevate yourself to the category of agentic people and be in that 20% of doers while others observe.

Wow did not expect to see a Marvel Rivals reference in this post.

Common theme in any domain: Just doing the obvious things puts you in the 90th percentile. I used to be extremely bad at chess, with a terrible rating after around 50 hrs of playtime against friends, but just 5 hours of deliberate practice learning openings and strategies put me head and shoulders above all of them.

I have been playing Marvel Rivals since it came out, and I have friends who really spend time grinding competitive and want to rank up but they don’t do the obvious things, such as reviewing a video of their gameplay, or watching a video for tips of their hero (or not blaming your team for every loss…)

Why is this? Why do humans fail to do the obvious things, and instead take suboptimal routes? Why is it so easy to get to the top 90th percentile in any domain?

This is a really good lesswrong post relating to this topic

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/PBRWb2Em5SNeWYwwB/humans-are-not-automatically-strategic

“it can potentially push your promotion forward by years.” Then you are on probation and get laid off by DOGE…. Sorry: couldn’t resist. Lol. Excellent read.